Editor’s Note: This is the third piece of a four-part series on the life and legacy of John Ball. You can read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

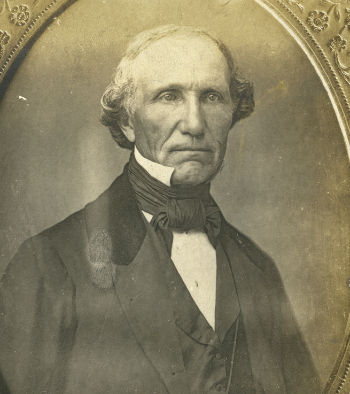

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — Like Louis Campau or Charles Belknap, John Ball’s name lives on in Grand Rapids. The man for which the city’s zoo is named lived a long, storied life, including adventures far beyond West Michigan.

But here in The Mitten State, Ball has an outsized legacy, making a deeper impact than many realize. Part 1 explored Ball’s early years. Part 2 shows how Ball found his way to West Michigan. His story continues with Part 3.

BOUND FOR MICHIGAN

By 1836, John Ball felt listless in eastern New York. After roughly three years of exploring, a quiet life in the northeast didn’t suit him. He had returned to practicing law but found business slow because other lawyers established themselves in his place while he was gone.

After more than a year in Lansingburgh, some friends and investors came up with an interesting proposal to cash in on America’s westward expansion and ignite the spark that once shined so brightly in Ball: Send the explorer westward to find and purchase some quality parcels of land.

“When they proposed the project, I fell in with it, for I was glad of an excuse for a change of life,” Ball wrote in his autobiography, “Born to Wander.”

The investors didn’t place too many restraints on Ball. They knew the best opportunities would be to the west and they wanted to avoid slave states. For everything else, they trusted Ball’s judgment to find the best investments. That led him to the Michigan Territory.

He left for his first journey to Michigan on July 27, 1836, accompanied by William Mann, another land prospector who had traveled that way before. The two took a train to Utica before picking up a boat on the Erie Canal and taking a steamer across Lake Erie from Buffalo to Detroit.

Ball assumed Detroit would be his primary focus, but quickly found that land prices were much higher than he expected. So the two men expanded their search, starting in Monroe and exploring other small villages in southeast Michigan and northwest Ohio. Mann eventually got sick and stayed back in Monroe while Ball ventured on for several more days. When he returned, Mann was nowhere to be found.

Considering the trip a bust, Ball returned home to New York. Instead of being bitter, his investors doubled down, giving him more funds to take another trip and expand his search.

He also heard from Mann. Through his brother, William Mann notified Ball that he recovered and continued on to the village of Ionia, where the government was set to open a new office to handle the “Grand River land district.” In late September, Ball left for Michigan once again, this time planning to head further west.

After arriving in Detroit, Ball followed the Territorial Road, a path laid by the government to guide followers from Detroit to St. Joseph on the shore of Lake Michigan. The road cut through Ann Arbor, Jackson, Marshall and Kalamazoo, an area that Ball said was “beautiful.”

“They had left the native forest on their lots and in the streets and had protected the same and planted others. … It had from its foundation always been the most beautiful,” Ball wrote.

Three days later, Ball had arrived in Ionia, acquiring more detailed maps of the land and what was available. With about $1,000 in his saddlebags, Ball headed off to a small village on the shore of the Grand River: a new town called Grand Rapids.

Ball arrived in Grand Rapids for the first time on Oct. 18, 1836. His first impression wasn’t a great one. Like Detroit, he found the land prices to be too high for his liking, with prices for lots along Canal Street (now Monroe Avenue) set at $50 per square foot. So just like Detroit, he explored the surrounding area instead.

He found and purchased some land in northeast Allegan County and western Barry County before returning to Grand Rapids to reorganize and prepare for a scouting trip to Ottawa County. The trip was a success but wasn’t without its hardships.

Ball’s primary goal was to find pine groves, which he did, in abundance. He and a companion, named in his autobiography only as Mr. Yeoman, had packed only one day’s worth of rations, but excited by their findings, pressed further into the woods. Snow slowed them down, and it took the men three more days to make their way back to nearby Grandville, where they could scrounge up a meal. An exhausted Ball noted that he had gone longer without food, but never while exploring on foot.

Days later, Ball, Yeoman and a third man took a second trip into the wild land — this time with a surplus of food — confirming their findings and purchasing approximately 2,500 acres of land.

Ball spent much of that winter scouting more locations across the state, including Muskegon County and more areas around Detroit. That spring, he returned to Grand Rapids, this time as a resident.

FROM OUTSIDER TO REPRESENTATIVE

Between Ball’s amicable personality and frequent travels, he was a popular person around the Grand River Valley. And when Michigan was formally recognized as a state in 1837, he was sent as the area’s representative to the state’s first convention that summer.

Later that year, he was nominated to represent the region in the new Michigan Legislature. Ball, the Democratic candidate, won easily over the Whig candidate.

According to Ball, about 500 votes were cast. He received more than 400 of them. Unlike now, when precincts are scattered all across cities, there were only five voting locations across the four counties Ball would represent: two each in Kent and Ionia counties and one in Clinton County. Voters in the sparsely populated Ottawa County, approximately 70 in all, traveled together by boat to Kent County to cast their ballots.

Ball didn’t particularly enjoy his time as a lawmaker. He would rather have been wandering in the woods than stuck at a desk, but in his short tenure as a legislator, he did accomplish some notable things, including ensuring all state tax dollars went to public school systems instead of splitting them with private, religious schools.

“I thought as far as the state was concerned it should have nothing to do with religious sectarianism,” Ball wrote.

With the legislature adjourned for the year and his land prospecting wrapped up, Ball decided to take a trip back to New England to update his investors and retrieve some final belongings, including his library of books. He was only gone for six weeks, but the trip and some miscommunication ultimately cost him his seat in the Legislature.

“The people at Grand Rapid seemed surprised to see me, saying they were informed that I had left for good,” Ball wrote. “For if they had known that I was coming back to stay, I should have been again nominated for the Legislature. This shows how careless I was on the subject.”

Instead, local Democrats nominated Col. Noble Finney in his place. Ball, showing no ill will, threw his support behind Finney’s campaign and helped him get elected.

His time in the Legislature was over, but Ball’s investment in education was not. He served on what would be considered Grand Rapids’ school board for 37 years and helped identify which property should be used for the city’s first school. The Old Stone Schoolhouse was built for $2,700 in 1849 at the northwest corner of Lyon and Ransom streets, now home to Grand Rapids Community College.

Ball also helped organize the Grand Rapids Lyceum of Natural History, a precursor to the Kent Scientific Institute, now known as the Grand Rapids Public Museum.

GROWING WEST MICHIGAN

In 1842, Ball was once again commissioned to explore the woods, this time on behalf of the state. The previous year, Congress passed funding to help states sell land and fuel development. Gov. John S. Barry tabbed Ball to lead the project for Michigan, identifying the best lands to allocate, putting them up for sale at a sharp discount.

Ball spent several weeks scouting vast swathes of the state, including almost all of northwest Michigan. The harsh travel conditions ultimately drove Ball to primarily choose land in the Grand River Valley. Not only was the land lucrative, but with established trails, they were much easier to reach. Ball reasoned that development in isolated areas would be much slower and defeat the purpose of the program. And he was proven right. Development in and around Grand Rapids grew exponentially in the following years.

Ball expected to be paid in cash for his work for the state and was frustrated to learn that he instead would be paid in shares of the land that he identified. Still, he was able to work that to his advantage, buying up some of the best properties that he had already scouted and worked the market to expand his property portfolio and accrue his profits.

With his experience as both a lawyer and as a land prospector, the new settlers coming to West Michigan also flocked to Ball for help. He worked as a de facto advisor, helping buyers through the process.

With a soft spot for farmers, he was also known for being patient and compassionate when they fell on hard times. Ball noted several instances of people falling behind on payments.

“When their money fell short, I often gave them time on my fees, or something more to enable them to secure their farms,” Ball wrote. “Or, if considerable lack, I would take the land in my own name as security, give them a receipt for the amount they paid on it, and when they paid the balance, assigned over the land.”

One of the most popular mass settlements in West Michigan occurred in 1847 when Rev. Albertus Van Raalte led a contingent of Dutch migrants to the region. Van Raalte worked with Ball to identify a place to settle.

Van Raalte allegedly rejected his first two proposals — Grand Rapids and Muskegon. Van Raalte wanted the settlement to be more isolated and the Grand River was too crowded. Muskegon, meanwhile, was too isolated.

“There would be only the wolves beyond them,” Ball wrote.

So they eventually landed on land around the Black River and settled what we know today as Holland.

HIS FINAL CHAPTERS

At the ripe old age of 56, John Ball finally “settled down.” Now firmly rooted in Grand Rapids, he got married on New Year’s Eve in 1850 to Mary Webster. The couple had six children: Frank, Kate, Flora, Lucy, Mary and John H. Ball.

But the family man didn’t sit around and watch the rest of his life go by. He still loved to travel, and took many adventures: some with his family, some with friends, and some on his own.

After the Civil War, he spent the winter of 1866 exploring the southern United States. In 1871, Ball finally took his long-awaited journey to Europe. According to his autobiography, the family set up shop in Geneva, Switzerland for two years, and spent time exploring, including many trips to Germany, Austria, Italy, France and Spain.

After a short illness, John Ball died on Feb. 3, 1884. He was 89 years old. His daughters noted that he was mentally and physically sharp right up until the end. A neighbor even recalled him running to catch a streetcar just weeks before his death.

With his death, came a promise he made with city officials years earlier. He planned to donate 40 acres of untouched land on the west side of Grand Rapids to be preserved as a park. Referred to as the “Ball Forty,” that land led to what we now know as John Ball Zoo and the former John Ball Park.

This is the third piece in a four-part series about the life and legacy of John Ball. The final piece will be published next Sunday.