Editor’s Note: This is the second piece of a four-part series on the life and impact of John Ball. You can read Part 1 here.

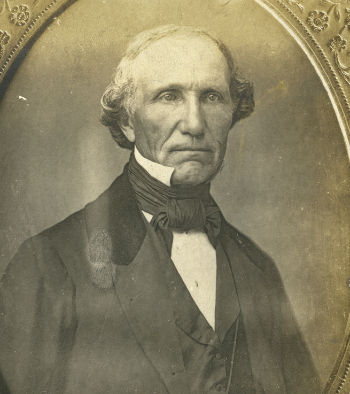

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — John Ball was 89 years old when he died in February 1884. It was a long life, but few people have packed more chapters into their story than Ball.

Here in West Michigan, his legacy lives on at the John Ball Zoo. His iconic statue still sits outside of the entrance. But his time in Grand Rapids is only one chapter in an epic tale. Part 1 of this series walked through his journey from life on the family farm to college and his first adventures around the young United States. The story continues below:

READY FOR ANOTHER ADVENTURE

In December 1831, Ball, then living in Lansingburgh, New York, was itching for another adventure and jumped at an opportunity when he learned of an expedition to the wild territory known as Oregon. The trip was led by Capt. Nathaniel Wyeth. After exchanging letters with Wyeth, the captain agreed to let him join the traveling party.

The party, however, wasn’t set to depart from Baltimore until March, so Ball had some time on his hands. The lawyer decided to use that opportunity to cross another big city off of his bucket list: Washington D.C.

He attended a session of Congress and listened in as the U.S. Supreme Court issued rulings. Ball also decided to take a chance and see if he could meet President Andrew Jackson, a politician whom Ball greatly admired. He had low expectations but went to the White House anyway and asked to meet him. Ball was surprised when Jackson agreed to it, saying he was “received kindly.”

The expedition took off from Baltimore, traveling by train when they could and on foot when they could not. Eventually, they picked up a steamboat that took them to Pittsburgh and continued on down the Ohio River, past Cincinnati and Louisville and eventually to St. Louis. From there, they moved to the Missouri River and rode the water to Independence, Missouri.

Independence is the infamous starting point of the Oregon Trail. But in 1832, the Oregon Trail was still in its infancy and hadn’t been fully cleared yet for wagons. Instead, Wyeth’s crew took the Santa Fe Trail, southwest to what is now New Mexico before turning north and heading for Oregon.

The trip had many highlights and lowlights. Ball loved the beauty of the plains and the mountains, and later recalled a day when he estimated he saw at least 10,000 buffalo. But the trek wasn’t all fun and games. In fact, Ball claimed he was one the only ones who didn’t regret the decision to take the trip. Many others routinely complained about the rough conditions and some turned back when the opportunity presented itself.

At one point, the group was forced to kill and eat one of its horses when rations ran low. Ball also detailed how the crew had to take turns swapping three-hour overnight shifts to keep an eye on the horses and watch for thieves and threats, namely nearby Native Americans.

The traveling party had several encounters with different tribes. Some were pleasant and the groups were able to trade supplies and food. Others, less so.

One of the men in the traveling party sparked a fight when the group encountered a group of Blackfeet Indians. According to Ball, the man’s father was allegedly killed by the Blackfeet. So when the group encountered them, the man went ahead to greet the chief in what appeared to be a civil manner. However, the man had hid a gun and when he came near, shot and killed the chief. Afterward, the man raced back to the group, bringing the rage of the Blackfeet with him. Six men with the traveling party were killed in the clash, along with many Blackfeet.

OREGON AND BEYOND

On Oct. 29, approximately seven months after it left, the expedition party reached Fort Vancouver in Oregon. Yet another trip of a lifetime was over, but not for Ball. He felt dissatisfied and didn’t want to travel all that way and not see the Pacific Ocean. So the next week, he trekked the final 100 miles to see the shoreline.

Ball and Wyeth were welcomed to Fort Vancouver by Dr. John McLoughlin, the regional leader for the Hudson’s Bay Company and “nominal governor” of Oregon. Ball didn’t want to impose on his hosts, so he asked McLoughlin what he could do to help. Because of his background as a teacher, McLoughlin thought it would be a good idea for Ball to offer classes to the young boys at the fort, including McLoughlin’s son.

That simple decision etched Ball’s name in Oregon history, becoming the territory’s first ever teacher.

With classes over for the spring, Ball decided to stake a claim of his own outside of Fort Vancouver and establish a farm. He built a humble log cabin, using cedar bark to seal the roof, noting that not a single piece of wood he used on the home was “sawed.”

While Ball was accustomed to farming, which he had grown up doing, he wasn’t accustomed to the isolation. In his autobiography, “Born to Wander,” Ball called that period a “primitive, lonely life.”

“My family consisted part of the time of a Mr. Sinclair, one of my mountain companions, a young wild native to catch my horses, and some of the time entirely alone,” Ball wrote.

After one season on the farm, Ball was ready to move on from Oregon. He knew one thing: he had no plans to tackle the Santa Fe Trail again.

“I saw no object of staying longer in the country, than for an opportunity to get away by sea. Once crossing the mountains and the plains I thought enough,” he wrote.

On Sept. 20, 1833, Ball left home and rode along on a Hudson Bay Company ship to the Pacific coast and down to the Mexican territory in San Francisco Bay. After a long stay there, the ship continued on toward the remote Sandwich Islands — now known as Hawaii.

If Ball was looking for new and exciting terrain, he found it on the Sandwich Islands. He was fascinated by the island’s volcanic mountains and spent lots of time exploring. He also noted the relative mix of populations there. In addition to the island natives, there were also traders and missionaries from the across the U.S., Mexico, China, Japan and even the Netherlands.

One of the merchants on the island befriended Ball and invited him to his Christmas dinner with King Kamehameha III. Ball noted that both the King and many of the natives spoke fluent English and “seemed entirely at ease.”

Ball admitted that he would have even considered settling down on the island had he found a decent career path. But when a whaling ship called the Nautilus came to port, bound for Massachusetts, he took it as a sign to move on and once again head home.

SAILING ON

Ball didn’t care for life aboard the Nautilus and, judging by his journals, it’s easy to see why. Early on, he suffered from seasickness and he thought his cabin, which he claimed was poorly ventilated and smelled horribly, was making him sick.

After enough nagging, the captain allowed Ball to sleep on deck. Sometimes, he even stashed away in a dinghy, using a sail to stay dry from the ocean spray and morning dew. After a couple nights of fresh air, his health improved.

The food supply was also a problem. Once the small stash of fruits and vegetables was gone, the crew was left with only 3-year-old provisions: salt beef that was “as hard as a brick,” musty flour and moldy bread.

And lest we forget the boredom. At sea for weeks at a time, there are only so many times you can watch a crew slaughter a whale. Ball was the only one on board with any books to read and it wasn’t a vast collection: a Bible, a book of poems by Lord Byron and a navigator’s guide.

He also didn’t care for the company. In his autobiography, Ball’s 19th century tongue seems to gloss over what is otherwise a harsh insult.

“It was a great change indeed, from the society of intelligent men and the agreeable family … to that of Captain Weeks,” Ball wrote. “He knew well how to sail a ship and to catch a whale, but little more.”

But there were a few highlights. The ship stopped in Tahiti and the Pitcairn Islands. Ball even ventured to Bounty Bay, where the infamous HMS Bounty was destroyed by a group of mutineers.

The Nautilus eventually made its way around Cape Horn, the tip of South America, and finally turned north. In early June, the ship reached port in Rio de Janeiro, ending a nine-week stretch between stops. Ball was elated, both grateful to be on land and grateful to be off of the Nautilus. He had no intention of returning to the whaler.

In Rio, Ball came across a few American soldiers and struck up a conversation. They introduced him to Lt. David Farragut, who was captaining a schooner called the Boxer back to Virginia. Because it was a military ship, Farragut couldn’t simply permit Ball to hitch a ride, but the amenable lieutenant came up with a solution. He hired Ball as his personal clerk, providing food and quarters in exchange for his work. His primary role was writing down the captain’s log, which took Ball an average of 15 minutes each day.

“(Time) passed pleasantly along,” Ball wrote. “The living a great improvement on that of the Nautilus, and the company ever pleasant and often instructive.”

It took the Boxer 38 days to reach Norfolk, Virginia, where Ball bid adieu to Lt. Farragut and his new friends. He took steamers from there to Baltimore, his former home in Lansingburgh and his family farm in New Hampshire.

HOME SWEET HOME?

Ball received a warm welcome. As far as the New Englanders knew, Ball was still in Fort Vancouver, building a new life in Oregon.

“They were all as glad to see me as though I had come from the grave, for they did not think it an equal chance that they ever should see me again,” he wrote.

A lot had changed since Ball left the northeast. His father, unfortunately, died a couple of months before his arrival. But his mother, 82, was still in “tolerable health.” Family aside, Ball noted in his writings how much railroads had expanded in those three short years.

“Oh! What a change had come over this part of the world since I left,” he wrote.

He returned to Lansingburgh and took a job with a law firm there but wasn’t inspired. Within a year, he was once again eager to explore. He contemplated heading back to Hawaii or maybe an adventure across Europe.

Eventually, a business proposition by some of his friends and neighbors grabbed Ball’s attention. He was heading to Michigan.

This is the second piece in a four-part series about the life and legacy of John Ball. The following two pieces will be published on Sundays over the next two weeks.