GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — A Grand Rapids-area business is donating equipment used during the Iraq War to the Smithsonian.

Consolidated Resource Imaging says it is having its counterterrorism work recognized by the museum. It is set to send the equipment to the Smithsonian Saturday.

“We happen to have a collection of camera systems from back when we first deployed in Iraq in 2005, 2006,” Nathan Crawford, the CEO, owner and founder of CRI, told News 8 Wednesday. “The Smithsonian found out we still had them and asked if we would be willing to donate them to the Smithsonian Institution for the Post Cold War section of the museum.”

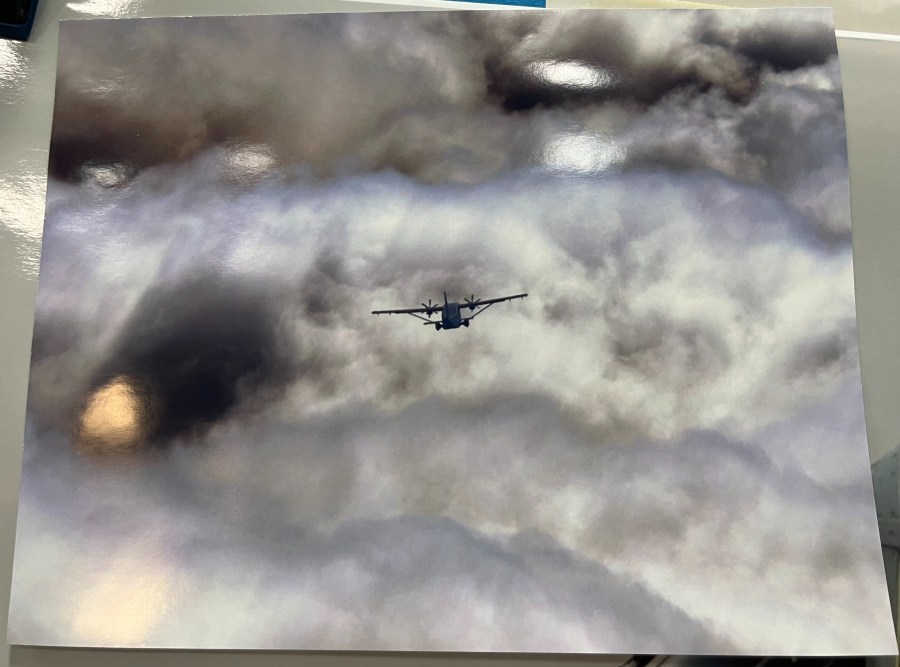

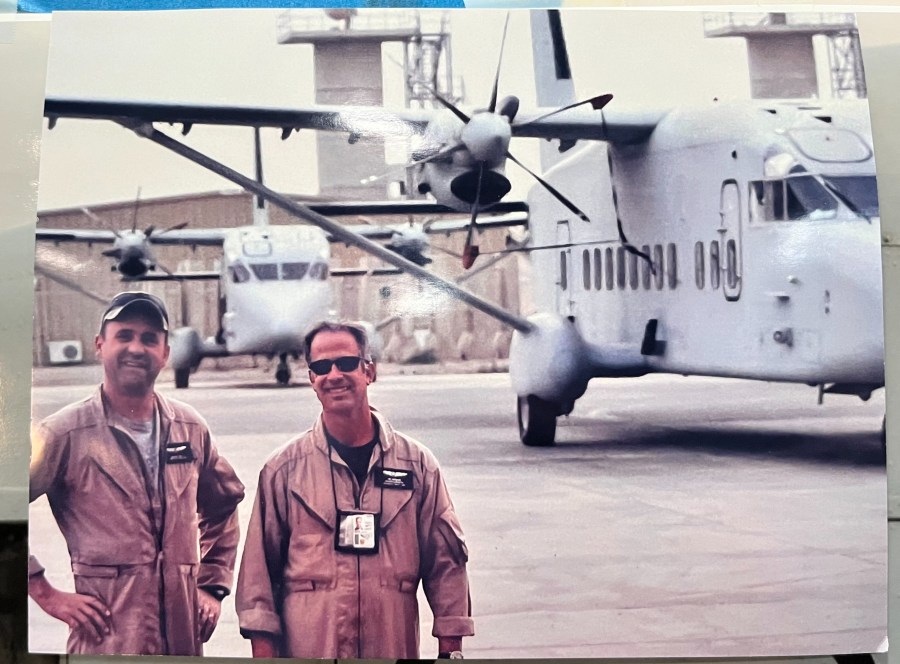

The camera systems were used in the Constant Hawk program, which used wide-area motion imagery technology to collect imaging of entire cities.

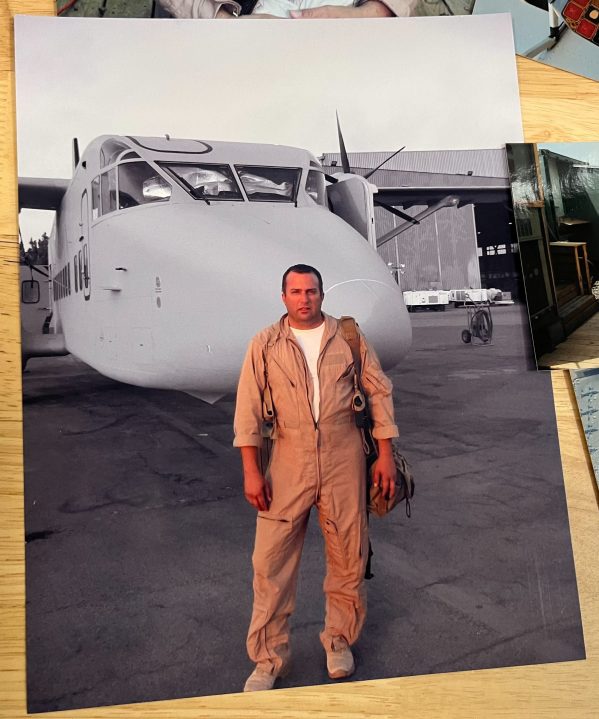

The team would be up in an aircraft for seven hours at a time in an unpressurized, freezing cold cabin collecting data. They would be on oxygen doing monotonous work, Crawford explained.

The contractor team — many of whom were veterans — was first deployed to Iraq for a 60-day test. When the program was first started, it was meant to help stop weapons of mass destruction getting into the U.S.

“Very quickly we had the challenge of IEDs in Iraq,” Crawford said. “We were losing 16 servicemen a day at the time, and they were throwing everything they could at the wall to see what would stick and see if they actually could figure out how to solve this problem.”

After a bomb went of, the team could use the data collected by the Constant Hawk program to backtrack with the goal of finding either those building or paying for the bombs.

After taking them out, “the entire network begins to unravel,” Crawford explained.

“You could actually find a single individual and actually stop them from making another 30 or 40 or 50 bombs,” he said. “The estimated number of lives saved was in the area of around 5,000 people, both in Iraqi lives and in U.S. soldiers’ lives being saved with this program through the data we collected.”

In a single flight, the team would collect 14 terabytes of data.

“We actually impacted the hard drive market for North America. They would literally take a semi-truck load of hard drives out of … (a) warehouse in Chicago, drive it up to the Milwaukee Air National Guard base and fly it directly to us in Baghdad,” he said.

From there, Crawford was tasked with formatting all the hard drives — around 3,000 to 5,000 in a shipment.

In the end, the crew collected a total of 6 petabytes, he said.

The team worked with the program for six and a half years in Iraq, a decade in Afghanistan and three years in Africa, Crawford said.

“It’s one of those things where you step onto that journey and you don’t know where it’s going to go and you have hopes,” he said. “We started in the film industry, and next thing you know, it’s Hollywood goes to war. And here we are in Iraq and Baghdad and Balad taking on this high-hard challenge.”

Crawford said the team was conditioned for it, as they had worked in “very austere environments” in the film industry.

“The added challenge was that this was a live combat zone, so you had indirect fire coming into our base, you had mortar rounds coming in, you actually had tracer rounds coming up at your aircraft — the kind of stories you don’t tell your wife,” he said. “But the bottom line is our team was a lot of prior service people and forming up this company and getting a chance to provide them with the opportunity to serve their country again, all of that rolled up into an amazing experience that’s just hard to explain.”

He said that type of technology is not in regular use right now.

“Heaven forbid we should need it here in the U.S.,” he said. “But we’re prepared for that possibility.”

Still, he said, it does have applications that could help society, though he said there would need to be laws and discussions on how to apply it.

“One of the things that I’ve always tried to march toward, I said, ‘I’ll hang my hat up and call it the end of the journey when I can stop an Amber Alert in progress,'” he said. “This is the kind of system that can do that.”

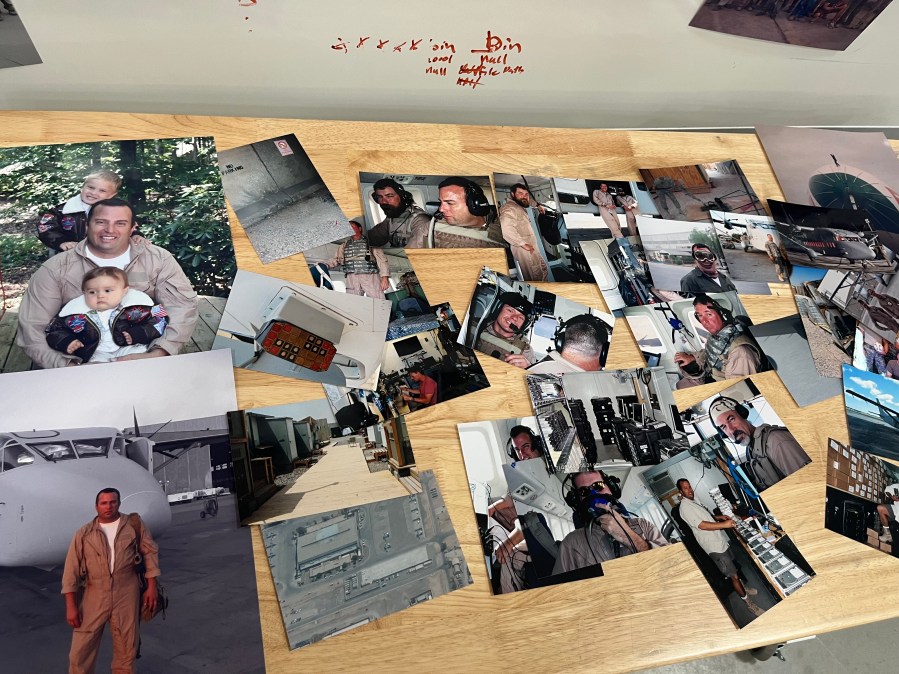

He said he’s excited to get the equipment to the Smithsonian. He said it was a three-year process, with the museum having teams reviewing it to decide if it was truly historical.

“They have historians and archivists, and everybody come in and they discuss this program and what we did and what we achieved,” he explained. “It was really up to just a few months ago we finally got the word that this actually was going to happen.”

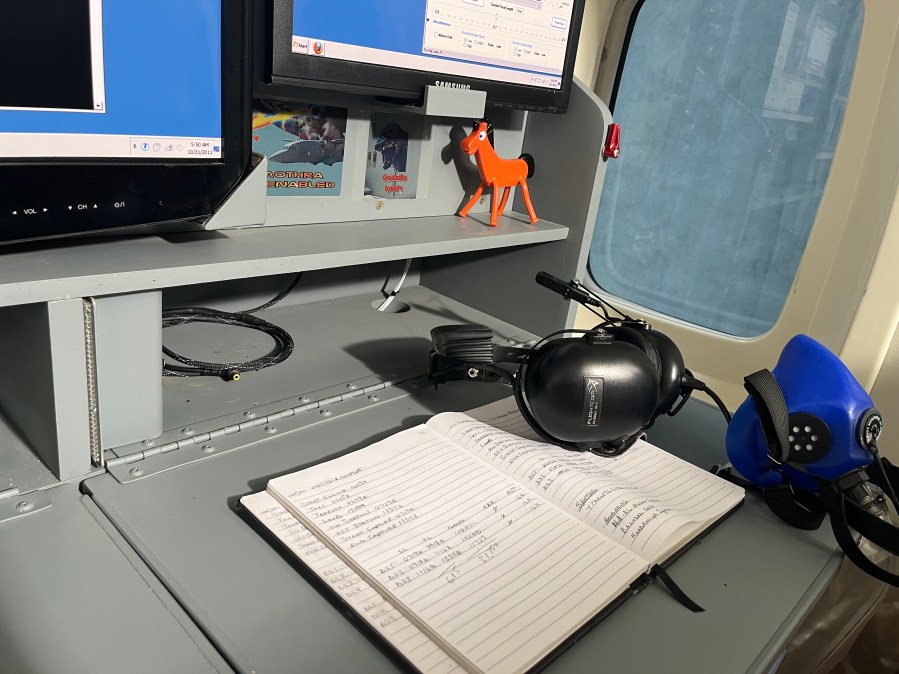

In the meantime, the team built a cross section of an aircraft, making it as close to the original as possible. There’s several original artifacts, like the camera, the gimbal, pressure chambers and chairs.

“The artifacts folks are really excited that they’re getting this much material,” he said.

There’s also a log book from a sensor operator who completed more than 580 missions, Crawford said, along with details like a Godzilla figurine and a hula dancer figurine.

He said those two pieces were in all the program’s aircrafts. The Godzilla was because the program became known as “Monster Island” due to its monster sensor, while the hula dancer was “tongue in cheek about the good times,” he said.

“They tended to accumulate the little things to kind of keep their minds going and keep them active through all those long hours,” he said. “(It was) really quite a privilege to work with them all.”

He said sending the equipment to the Smithsonian feels like the period at the end of a sentence. Still, when asked what emotions he’s feeling as he gets ready to send the equipment to the museum, he told News 8, “That’s a very loaded question.”

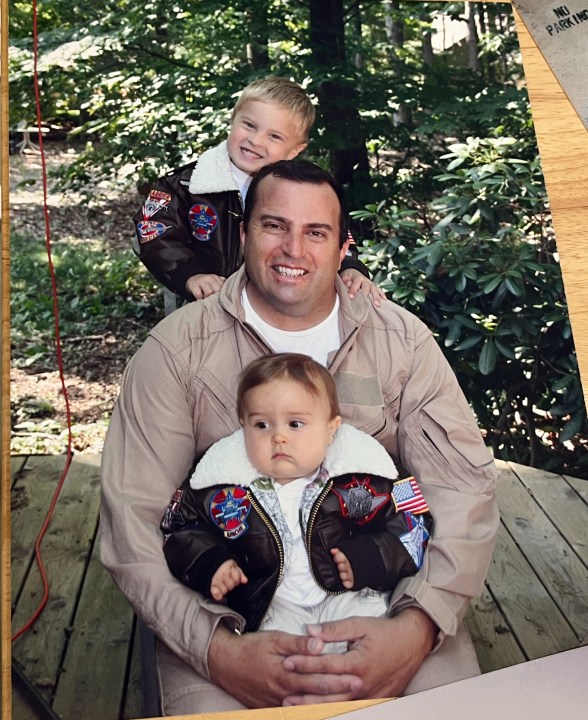

“This was very hard on everybody. It was very hard in my family. I had two young sons at the time and to go off and commit to this — it was extremely hard on my wife. We just had our 36th anniversary, so we’re really happy to have made it through all this, but it’s not an easy journey, and that goes for everybody,” he said. “But … really what a blessing to actually have the opportunity to serve in this way, to be on the edge of history, on the edge of current events, on the edge of technology all at one time, it was unbelievable.”

“It was quite a ride,” he continued. “I often said to people it felt like you had the winning lottery ticket in your hand in the middle of a forest fire, drinking from a fire hose. I mean, it was just a very intense journey. And so in that regard, a lot of emotions, a lot of feelings about the whole thing. And I’m just proud to have the opportunity to deliver this on behalf of the whole team.”