GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (WOOD) — Recent test results have put the site of a former Grand Rapids landfill on the radar of the Michigan PFAS Action Response Task Force.

MPART published documents late last week declaring Butterworth #2 Landfill an official PFAS contamination site. Sampling conducted across the site in June found multiple results with PFAS levels exceeding safety standards.

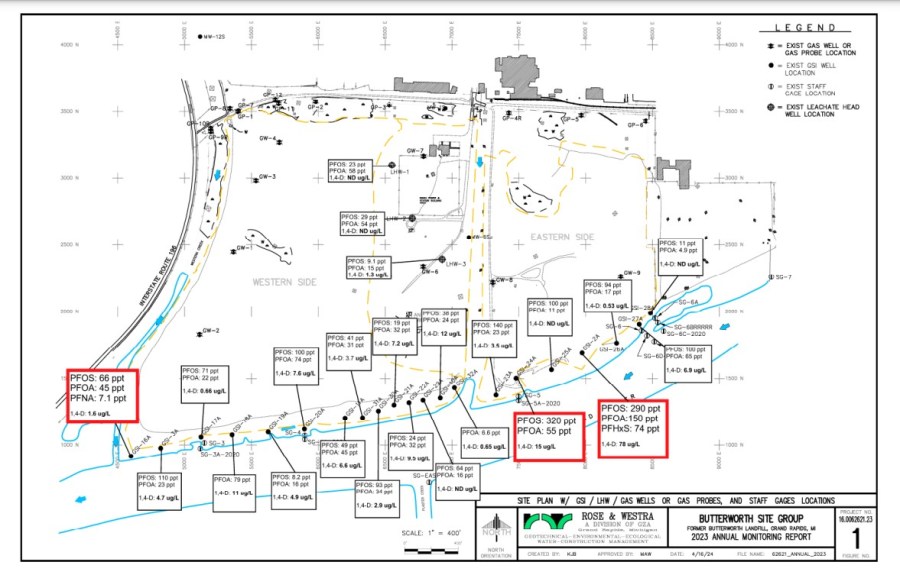

In particular, three wells along the Grand River showed the worst results. One showed 320 parts per trillion of PFOS — perfluorooctane sulfonate — well above the safety standard of 16 ppt. That same well also showed 150 ppt of PFOA — perfluorooctanoic acid — and another showed 74 ppt of PFHxS — perfluorohexane sulfonic acid. The safety standards for those are 8 ppt and 51 ppt, respectively.

On the 180-acre site, 120 acres were used as a dump from 1950 to 1967 and then again as a sanitary landfill from 1967 to 1973. It was eventually shut down by state officials who had uncovered what the Environmental Protection Agency described as “improper operations.”

The former landfill was first recognized by the EPA as a prioritized site in 1983. The site’s landfill cover was upgraded and monitoring systems were put in place between 1999 and 2000, with the EPA set to monitor the site for at least 30 years.

According to MPART, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy requested the EPA start sampling the landfill for PFAS contamination in 2019 because of the site’s history of accepting waste from known contaminators, including Wolverine Worldwide and plating companies.

The site, 1450 Butterworth St., sits to the east of I-196 on the northern border of the Grand River, not far from the confluence of Plaster Creek. The site’s groundwater feeds multiple wetlands and small ponds on the property and flows directly into the Grand River.

PFAS — or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — are a large group of compounds first developed in the 1940s and incorporated into all sorts of products for waterproofing and heat resistance. Decades later, research showed that PFAS compounds take a long time to break down organically and can build up in the human body, causing serious health problems including cancer.

According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Services, there are more than 15,000 known PFAS compounds.

The Environmental Working Group says there are now more than 5,000 confirmed PFAS-contaminated sites across the United States, including at least one in all 50 states, Washington D.C. and two American territories.